It has become very common for family members to fight themselves on the death of the original family head because of the distribution of the property left behind and who is to become the next family head. This piece offers a glimpse into the position of customary laws guiding how a deceased person’s property is shared in Yoruba and Bini lands.

The reason for such fights or arguments arises where the original family head has not validly made a legal will, expressly stating how his property is to be distributed and who should oversee the affairs of the family. In order to curb all of these arguments and fighting whenever they arise, the law has provided for a lasting solution, per adventure the head of a family dies without stating who should inherit his property and who is to oversee the affairs of the family.

Now, the general rule as against the decision of the court in the case of Salubi v. Salubi is that on the death of a person who has not made a will and is married under the Marriage Act, the applicable law to govern the distribution of the deceased property is state law and federal or English law. This means that, wherever the property is situated, the property will be distributed according to the law of the state where the property is. See the case of Obusez v. Obusez.

As regards customary law, under the Yoruba customary law, the basic principles were enunciated in the case of Lewis v. Bankole and have continued to remain relevant, valid and applicable.

It is that, on the death of the founder family, the eldest son, called Dawodu succeeds to the headship of the family. Now, on the death of the eldest surviving son, the next eldest surviving child of the founder, be it a male or a female, succeeds as the head of the family.

See the case of Amusan v. Olawuni. As regards the property owned by the founder of the family, the property devolves on all his children irrespective of sex. It should be known that blood relations of the founder of the family such as brothers, sisters, uncles do not have a place in the distribution of the said property. Before any dealing with the property, all branches of the family must be consulted.

The representation of the family council is per stripe, according to the number of wives with children.Two modes of distribution exist under the Yoruba customary law which are- idi igi and ori ojori.

The idi igi means distribution according to the number of wives while ori ojori is distribution according to the number of children. It has been suggested that where the deceased has only one wife then the applicable mode should be ori ojori and where the deceased has more than one wife, then the applicable mode should be idi igi. Again, it should be known that a widow cannot inherit her deceased husband’s property nor could she be appointed as an administrator of her late husband’s estate under the Yoruba customary law.

This was the position of the law in the case of Ologunleko v. Ikuemelo. Under the BINI customary law, it was upheld and affirmed in the case of Arase v. Arase that; the eldest son of the deceased person does not inherit the deceased property until after the completion of the second or secondary burial ceremonies.

The completion is marked by a ceremony by members of the family called “UKPOMWAN” this ceremony is performed for the eldest son. It is only after this ceremony that the family distributes the property of the deceased. Upon distribution, all the property of the father, that is, all the property owned by the deceased automatically becomes that of the eldest son.

The principal house in which the deceased lived in his life time and died is called the “Iguobe” it always passes by way of inheritance to the eldest son. In the case of Ovesieri v. Osagiede, it was held that neither the eldest son nor any other relative could administer or succeed to the estate. When the eldest son fails to perform the second rites of his father, he holds the estate of his father in trust for himself and his brothers but the Iguobe will not be vested in him.

The above goes to show how important the performance of the second rites of the deceased by the eldest son is. It should be known that the iguobe is the principal home where the deceased lived, died and was buried. It is not just merely a piece of land.

The iguobe must be owned absolutely by the deceased father during his lifetime. It has been decided in the case of Eghrerba v. Omonghae that there is only one Iguobe and it must be located within the Bini kingdom. Only the ancestral home of the deceased will constitute iguobe and not a rented house.

In the case of Agidigbi v. Agidigbi where the deceased owned three buildings erected on the same piece of land but resided, died and was buried in one while one was rented out and the other remained unoccupied, the court held that only the building occupied constituted the iguobe.

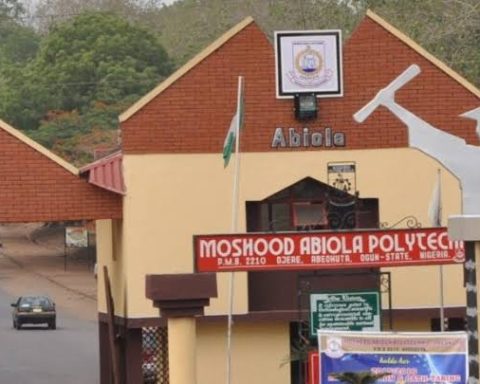

Next week Sunday, we shall continue the discussion on other customary law such as the Ibo customary law. LEGALJOE who is also JOSEPH ALIU is a Law Undergraduate, Oou chapter and can be reached via; 09131704196, 09085773212, aliujoseph085@gmail.com